Venus is the second planet from the Sun, historically known as the “Morning Star” or “Evening Star” due to its brightness in the early morning or late evening sky.

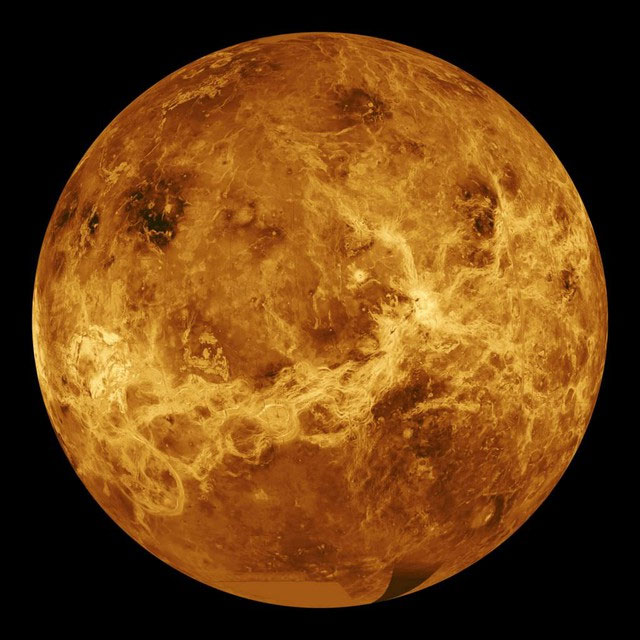

Venus shares many similarities with Earth in terms of volume, mass, and density, often earning it the title of Earth's “twin sister.” However, its surface is a literal hellscape, with temperatures reaching hundreds of degrees Celsius, atmospheric pressure 90 times that of Earth, and an atmosphere filled with carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid vapors.

In such an environment, the existence of any life is deemed impossible, and even the survival of artificial devices is extremely challenging. Yet, it was precisely this inhospitable planet that captivated Soviet space explorers.

Between 1961 and 1984, the Soviet Union launched a total of 26 Venus probes, 18 of which successfully landed on the planet's surface. These missions set multiple space exploration milestones and provided invaluable data and images that significantly expanded humanity’s understanding of Venus.

The origins of the Soviet Venus program trace back to the late 1950s. At that time, the Soviet space industry had already achieved global recognition with milestones such as launching the first artificial satellite, sending the first cosmonaut into space, and completing the first space docking.

Sergei Korolev, the chief architect of the Soviet space program, believed that exploring other planets in the Solar System was a crucial goal of space exploration. Venus was considered the most suitable target due to its similarity to Earth and its relative accessibility.

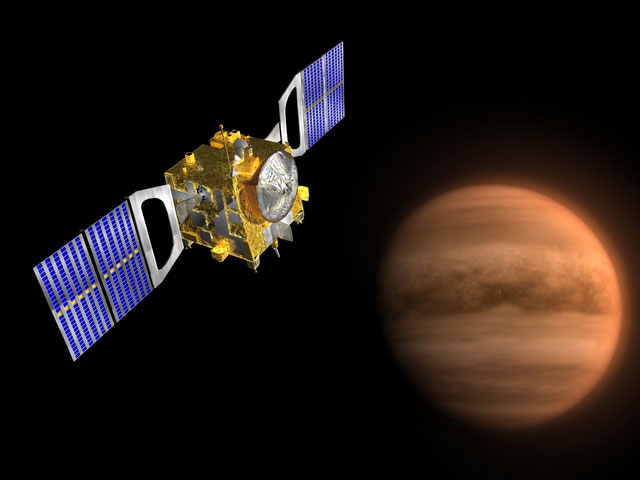

Korolev aimed to unravel the mysteries of this planet by studying its origins, evolution, and potential habitability, while also preparing for future human landings and colonization. To achieve these objectives, the Soviet Union designed a diverse range of probes, including flyby spacecraft, orbiters, atmospheric probes, and landers, as well as hybrid probes combining multiple functions. These probes were collectively named the “Venera” series, sequentially numbered from 1 to 16.

Additionally, there were several probes without official designations, such as Venus 1VA and Kosmos 482, as well as joint projects with other nations, including the Vega Project and the Venus-Halley Detector.

On February 12, 1961, the Soviet Union launched Venera 1, the first probe in human history dedicated to Venus exploration. Initially planned to perform a flyby and collect atmospheric and magnetic field data, the mission suffered a communications failure mid-flight and could not complete its objectives.

Of the next three launch attempts, only Venera 4 successfully penetrated Venus’s dense cloud layers, entering its atmosphere and transmitting critical environmental data. In response, the Soviet Union began developing probes capable of withstanding Venus's extreme atmospheric pressure and harsh conditions. These probes featured titanium shells and high-performance shock absorbers to protect internal instruments upon impact.

In 1970, the Soviet Union successfully launched Venera 7. As the probe entered Venus’s atmosphere, it descended to approximately 60 km above the surface. However, due to the unknown environmental complexities and technical limitations at the time, the Soviets had to rely on previous atmospheric data for deceleration and parachute deployment rather than using onboard engines for controlled descent.

Unfortunately, the immense atmospheric entry velocity caused the parachute to tear apart after just six minutes. Ultimately, the probe crash-landed at nearly 60 km/h, transmitting signals for only one second. This was the first time humanity had ever detected a signal directly from Venus’s surface.

This second transmission brought an astonishing revelation: Venus's surface atmospheric pressure was 90 times that of Earth, and temperatures soared to nearly 500°C—hotter than Mercury. From that moment, humanity’s perception of Venus shifted from that of a “beautiful goddess of love” to that of a terrifying inferno.

The Soviet exploration of Venus did not end there. On March 5, 1981, the Soviet Union launched Venera 13, an advanced, optimized spacecraft consisting of an orbiter and a lander.

The mission aimed to conduct in-situ research on Venus's surface. After navigating through its dense atmosphere, Venera 13 successfully landed in the Phoebe region near the equator and captured a color image that shocked the world.

The image revealed a yellow, desert-like terrain, battered by sandstorms and devoid of any signs of life, evoking a hellish desolation. The probe also used a drill to extract rock samples from the surface and conducted X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy analysis on them.

However, due to Venus’s extreme conditions, Venera 13 could only operate for two hours before losing contact with Earth. On June 7 of the same year, the Soviet Union launched Venera 14.

This probe was similar to Venera 13 but carried slightly different scientific instruments. The lander remained functional for 57 minutes, during which it transmitted eight images—one of which was a color photograph of Venus’s surface—along with atmospheric and surface data.

The images revealed rocks, sand, debris, and structures resembling lava flows. The lander also analyzed Venusian soil, uncovering information about its chemical composition and radioactive elements. Eventually, the probe ceased operations due to battery depletion.

Following a series of groundbreaking discoveries, humanity gained deeper insights into Venus and a heightened sense of awe for the planet. Venus’s atmospheric pressure alone is lethal to humans, and its atmosphere consists of over 95% carbon dioxide, generating an intense greenhouse effect that keeps temperatures near 500°C.

Furthermore, Venus’s atmosphere contains significant amounts of sulfuric acid vapor, leading to frequent acid rainstorms on the planet’s surface. Such an environment can only be described as hellish and terrifying.

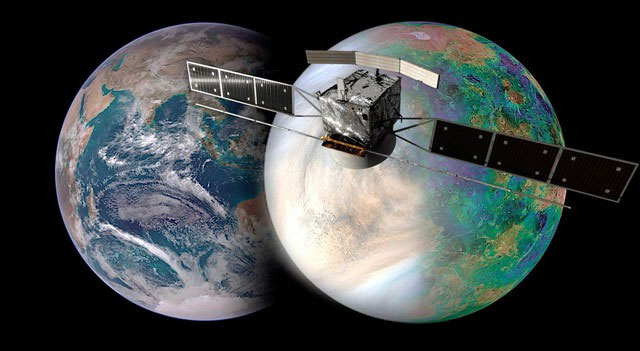

In later missions, the Soviet Union shifted its focus to orbital observations and mapping of Venus rather than attempting further landings.

The Soviet Venus Project was an ambitious, “crazy,” and groundbreaking endeavor in space exploration. It left an indelible mark on space history and a profound impression on humanity. It was a masterpiece of Soviet space engineering and a milestone in humanity's journey into the cosmos.

This was the first major exploration of Venus by humankind and significantly advanced our understanding of the planet. Although the Soviet Venus Project has concluded, humanity’s interest in Venus remains strong. With growing curiosity, advancing technology, and increasingly sophisticated equipment, the exploration of Venus is poised to enter a new phase.