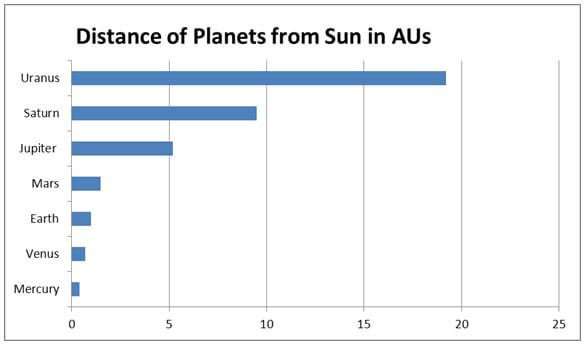

Until the hypothetical ninth planet is discovered, Uranus remains the most “unusual” planet compared to the other seven planets in our Solar System.

On January 24, 1986, the unmanned interplanetary spacecraft Voyager 2 passed by Uranus on its journey beyond the Solar System. This was the first and only time we visited this gas giant. Uranus occupies a very peculiar position within our Solar System.

The Discovery of Uranus

In ancient times, scholars only recognized the existence of six planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn—those visible to the naked eye. It was only with the invention of advanced telescopes that humanity discovered additional planets in the Solar System.

Although Uranus can be seen with the naked eye and has been observed throughout history, ancient people mistook it for a star rather than a planet. It wasn't until March 13, 1781, that astronomer William Herschel observed Uranus and initially believed it to be a comet. He described his observations as follows:

“The first time I observed this comet, my telescope had a magnification of 227. Based on my experience, I knew that the diameter of fixed stars does not increase with magnification, but planets do. So, I increased the magnification to 460 and 932 and discovered that the diameter of this comet increased proportionally with its brightness. This suggested that it was not a fixed star, unlike the other stars I used for comparison, whose diameters remained unchanged.

Moreover, through my telescope, the comet appeared much brighter than expected, giving it a hazy and indistinct appearance under high magnification. In contrast, stars usually maintain their brightness and sharpness, which I have confirmed through thousands of observations. This evidence strongly supported my hypothesis that it was indeed a comet, as later observations also suggested.”

Note: Although the Vietnamese term sao chổi (comet) includes the word sao (star), a comet is not a true star. Comets are celestial bodies that move within the Solar System, typically following parabolic or highly eccentric orbits. As they approach the Sun, they brighten and develop tails due to solar radiation, becoming more visible. Conversely, as they move away from the Sun, they dim and eventually become nearly invisible at their farthest points.

The Name “Uranus” and Its Controversy

It was only when Herschel shared his discovery with another astronomer, Nevil Maskelyne, that they realized it was not a comet but a planet orbiting the Sun. Observations from other astronomers confirmed this, and Herschel was given the honor of naming the planet. He named it Georgium Sidus (“George's Star”) in honor of King George III.

However, this name was not well received by the European astronomical community. In 1872, German astronomer Johann Elert Bode proposed the name Uranus, a Latinized version of the Greek god Ouranos. Nevertheless, it took several decades before this name became widely accepted.

The discovery of a new planet was a groundbreaking event in astronomy, sparking a race to explore other planets within the Solar System.

The Orbit and Tilt of Uranus

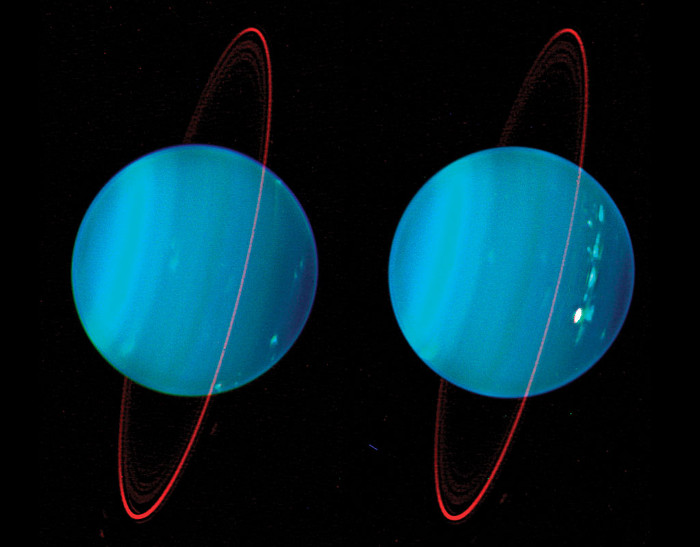

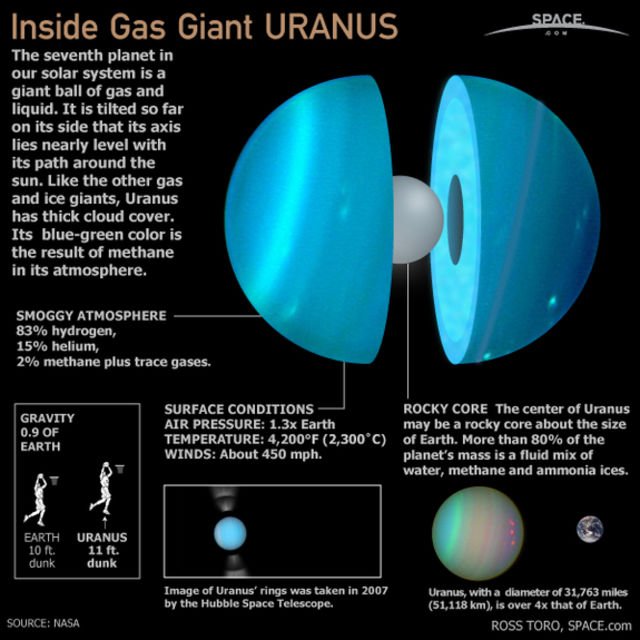

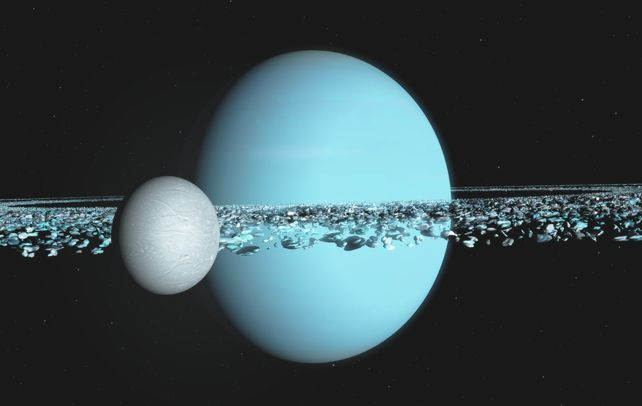

Over the following centuries, astronomers studied Uranus's orbit, discovering its five major moons, its ring system, and its unusual axial tilt. Unlike other planets in the Solar System, Uranus has an extreme axial tilt of 97.77°, causing one of its poles to face the Sun.

However, it wasn't until the 20th century that Uranus began to receive significant attention from the astronomical community.

The Voyager 2 Mission

In 1965, Gary Flandro, a student at the California Institute of Technology and a researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, initiated a project to map potential targets for future NASA missions. He focused on Uranus and plotted its orbital path to assess possible exploration opportunities. He soon realized that “Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune would align on one side of the Sun in 14 years,” as described by Jay Gallentine in Ambassadors from Earth: Pioneering Voyages of Unmanned Spacecraft.

This was the first step toward recognizing a new space exploration program—Voyager. This ambitious project led to the development of two spacecraft designed to explore the outer reaches of the Solar System.

In 1977, both Voyager spacecraft were launched toward Saturn. Voyager 1, launched on September 5, flew past Jupiter and Saturn before continuing out of the Solar System. Voyager 2, launched on August 20, followed a different path, passing by Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune before leaving the Solar System.

On January 24, 1986, Voyager 2 reached its closest approach to Uranus, at a distance of 50,600 miles (approximately 80,000 km) from the planet’s surface.

Discoveries About Uranus

During its visit, Voyager 2 uncovered a wealth of new information about Uranus. In addition to studying previously discovered moons—Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon—it also detected several new moons, including Cordelia, Ophelia, Bianca, Cressida, Desdemona, Juliet, Portia, Rosalind, Belinda, Perdita, and Puck.

The probe also made fascinating discoveries about Uranus’s atmosphere. The weather on Uranus is extremely cold, with its atmosphere primarily composed of hydrogen and helium. One of the most significant findings was its strange magnetic field.

Voyager 2's encounter with Uranus lasted only 5.5 hours before the spacecraft continued toward Neptune, using Uranus’s gravity to assist its journey.

Future Exploration of Uranus

Since then, humanity has continued studying Uranus. We have observed auroras in its atmosphere and discovered that its climate is experiencing sudden warming. However, much remains unknown about this enigmatic planet.

As of now, no further missions have been sent to Uranus. While several proposals have been made, none have received as much priority as missions to Mars, Jupiter, or Saturn. As of 2015, NASA has begun considering a new mission, potentially set to launch in the 2020s. A future Uranus mission may require an orbiter, which could provide more detailed information about this mysterious planet.